Faker Elmyr de Hory by hoaxer Clifford Irving: an Ibiza-based Netflix series?7th February 2023

The story of legendary Hungarian art forger Elmyr de Hory and American literary hoaxer Clifford Irving, who both lived in Ibiza in the anything-goes 1960s, has all the ingredients for a gripping, twisting and turning, sundrenched Netflix series.

When I interviewed Barney Irving, Clifford’s son, notorious for faking the autobiography of eccentric billionaire recluse Howard Hughes, he mentioned that the streaming giant was considering a script about Elmyr’s life written by his father.

Ibiza was where Clifford conceived of and carried out the hoax, which landed him in prison for 17 months. In all the accounts I’ve read of what transpired, no-one has ever considered the part the White Island itself played in his actions.

How Clifford met Elmyr

First visiting Ibiza in 1953, Clifford Irving settled on the island in 1962. He was among the American writers who, as Stephen Armstrong puts it in his excellent The White Island: The Extraordinary History of the Mediterranean’s Capital of Hedonism ‘were fleeing McCarthy and the Korean War and followed Hemingway’s dreams to Spain, drifting down to the Balearics because of the promise in New York circles that “in Ibiza you can live forever on credit”.’

The Ibicencan tolerance of outsiders and tradition of not asking questions or passing judgement also attracted shady character such as Hungarian-born art forger Elmyr de Hory – real name Elemér Albert Hoffman – who washed up on the island around 1960.

‘Elmyr fitted comfortably into this community of dissolute artists, freaks, drinkers and stoners,’ writes Stephen Armstrong. ‘For the first time in his life, he felt at home. He would drift between tables at the crowded dockside bar, chatting with the other artists.’

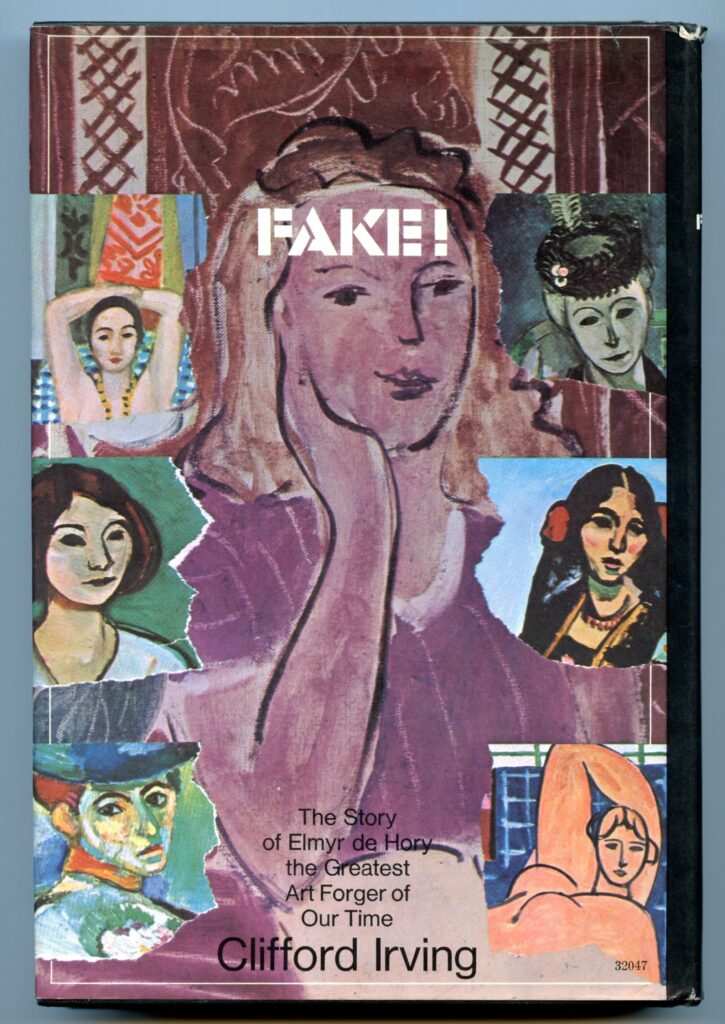

Called ‘the greatest forger of the 20th century’ by his biographer Clifford, Elmyr is reputed to have sold over 1000 art forgeries worth over $50 million in today’s money to reputable art galleries worldwide.

In June 1965, Elmyr moved into a house he had built for himself that he named La Falaise – The Cliff – in the Los Molinos district of Ibiza Old Town, possibly either at Carrer al Sabina 48 or Carrer de Luci Oculaci 48. Established at La Falaise, Elmyr settled into a lavish lifestyle of never-ending glamorous parties and dinners, funded by sales of his forgeries.

After serving two months in Ibiza Town’s laidback prison in late 1968 for the crimes of homosexuality, having no visible means of support and consorting with criminals, Elmyr was expelled from Ibiza for a year. When he returned, he told his story to Clifford.

Clifford Irving: last of the swashbuckling writers

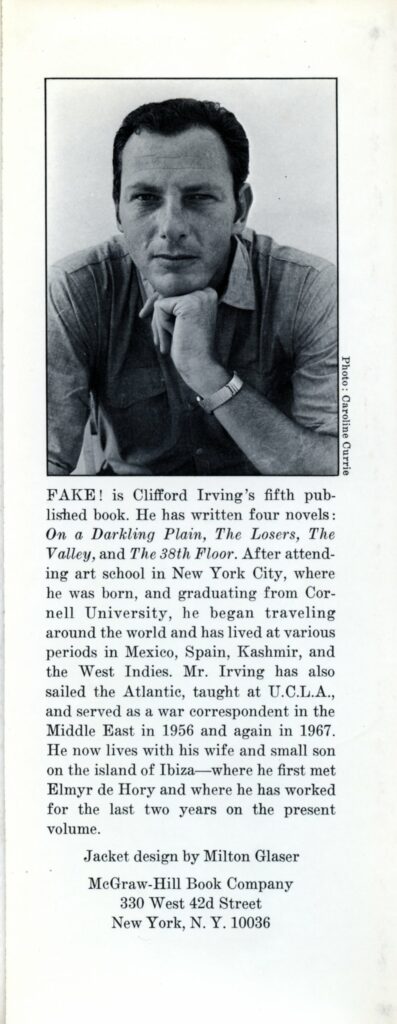

Clifford Irving was born on 5 November 1930 and grew up in New York. He attended Manhattan’s prestigious High School of Music and Arts, graduated from Ivy League Cornell University with honours in English and published 20 novels.

Married six times, Clifford was described by the editor of one of the magazines for which he wrote as ‘the last of the swashbuckling writers’. He was 6ft 3in, weighed 250lbs and had size 16 feet.

Today, Clifford is best known for the faked autobiography of Howard Hughes, the backstory of which he describes in his 1981 book The Hoax, made into a 2006 movie starring Richard Gere.

The Hoax purports to tell the story of how Clifford, along with his co-hoaxer fellow US writer Richard Suskind came to write the fake autobiography, abetted by Clifford’s Swiss wife Edith.

A gorgeous literary caper

Despite the fact that Clifford bargained his publishers McGraw-Hill up to $765,000 (roughly $5.5 million today) for his advance and fee, he claimed money wasn’t the point.

In The Hoax, Clifford writes that he saw the fake Hughes autobiography as ‘a gorgeous literary caper, in which publisher and author would collaborate’. As McGraw-Hill weren’t in on the hoax, this rationale seems a bit dubious.

He also insists that he and co-writer and conspirator Richard Suskind had no intention of keeping any of the money McGraw-Hill paid them so no-one would be hurt.

Elsewhere in the book, he suggests that his publishers somehow asked to be conned. ‘They want it so bad I could hear them salivating four thousand miles away,’ he writes.

But Clifford also writes that he committed to going ahead with the hoax because it was a pure challenge, like climbing in the Himalayas. He simply wanted to see whether he could get away with it. Given that Clifford appears to have been a man with an enormous ego, this is the only explanation that might remotely ring true.

In the expat milieu of Ibiza that Clifford loved, where he felt at home, where the hoax was cooked up, where shadiness was accepted if not admired, where no questions were ever asked and judgement never openly made, his motivation would have been, in any case, irrelevant.

But there were consequences to his actions and those of his co-conspirators. When Clifford, Edith and Suskind admitted to the hoax, all three went to prison. Together they owed well over $1.5 million to McGraw-Hill, the IRS and their lawyers. Clifford’s ‘reputation as a writer was crippled; I was known as a liar and a con man; I had achieved – and hardly by design – not fame but notoriety,’ he writes.

Barney Irving and the legacy of the hoax

The youngest of Clifford’s two sons with Edith, Barney Irving was born in Barcelona in 1970 when the Howard Hughes hoax was well underway. He was just two years old when his mother and father went to prison.

‘It was a gentleman’s crime that just ended up going a little too far,’ Barney, who divides his time between Ibiza and the US, told me.

While, on the face of it, Clifford doesn’t seem to have suffered too much from the failure of the hoax and doing time in prison, things were far harder for Edith, who helped deposit advance payments for the fake Hughes autobiography in Swiss bank accounts.

Edith received a longer sentence for her part in the crime than either Clifford or Suskind, Clifford’s supposed researcher for the book.

‘My mom was prosecuted by the Swiss,’ Barney explains, ‘and they wanted to make an example of her: don’t mess with us. She served two years and four months while my dad did under two years and she hers were much harder time. She also wasn’t allowed to see my older brother John-Edmund and me.’

An Ibiza childhood

For some of the time they were apart from their mother, Barney and his brother were cared for by a simple Ibicencan country woman, permanently dressed in mourning black. He has fond memories of simple Ibiza country life ‘drawing water from the well, catching rabbits, chopping the heads off chickens and plucking their feathers.’

When his father was released, Barney was four. Clifford went to Mexico but Edith returned to Ibiza, where Barney grew up in the finca that belonged to her. His stepfather was a lawyer from New York named Bill Maloney who was, according to Barney, ‘very strict’.

Despite this, Barney had a wild childhood. ‘By the time I was fourteen,’ he told me. ‘I would head off on my motorbike and not come back for three days. But, although life was carefree, it could be rough on us children. I have friends who grew up on the streets.’

Having a mother and father who had spent time in prison wasn’t the stigma it might have been elsewhere. ‘Some of my friends’ parents were put in jail for smuggling hash from Morocco. It was very, very common,’ Barney told me.

Ibiza in his blood

Barney sees the good and bad sides of how he grew up. ‘The advantages are that I have my father’s genes and can just pick up and go, land somewhere I don’t know anyone and find a job and a place to live. I’m also resilient. I’ve been homeless a few times and always been able to get out of that situation. Being fluent in Spanish as a result of growing up in Ibiza has been really useful. And, of course, when people find out who my father was it’s a great topic of conversation.’

‘But in the end,’ Barney continues, ‘I decided to just be who I am. Now, I think it was a great advantage to grow up in Ibiza with the parents I had. They didn’t set out to intentionally hurt my brother and me. I’m very proud of my background and I’ll never get the island out of my system.’

Edith left the family finca to Barney and his brother and he returns to the island as often as he can to paint and sculpt and hang out with the farmers and the locals in a ‘little country store somewhere that I’ve ridden out to on my Triumph motorcycle.’

When I asked Barney why he thought his father had gone ahead with the hoax, he said ‘I think it was a gentleman’s crime that went too far.’

Elmyr’s story as a mini-series?

Now it seems the stories of Irving and Elmyr de Hory could be reaching a new generation.

When Barney was cleaning out Edith’s finca after she died, he uncovered a script written by Clifford and based on Fake, his biography of Elmyr. Barney’s brother John, a voice-over artist who lives in Berlin, sent the script to Netflix and there’s a possibility of it being made into a mini-series.

Which, for those of us fascinated by Ibiza’s colourfully shady past, would be a treat.

If you’re curious about Elmyr’s story and would like a taste of what Ibiza was like in the 1960s, Orson Welles’s superb F For Fake movie features Elmyr and Clifford.